Harlin McEwen, Village of Cayuga Heights Police Chief, 1972-1985

Oral History Interviews, January 16, March 3, and July 20, 2020

Conducted at the McEwen Home, 422 Winthrop Drive, Ithaca, by Village of Cayuga Heights Historian, Beatrice B. Szekely (BBS)

First Interview: The Setting, Early Life and Career

The Setting

We met in a large and comfortable room in the lower level of the McEwen home on Winthrop Drive in the Town of Ithaca, right across the street from the Northeast Elementary School. In the past this was the living room of a two bedroom apartment; now it’s the retired police chief’s office. We were seated at what once served as a dining table. Across the room a large desk under a window faces Winthrop Drive, where Harlin would normally be seated in the middle of the afternoon. Computing equipment is prominent as befits the occupant who, over the course of a sixty-year career, played a leading role in the development of radio and computer communications systems for law enforcement and public safety. When I arrived, the local police, fire and emergency dispatch system was turned on. Before we got down to the business at hand, I took a moment to look at the many awards and decorations covering the walls of the room in recognition of a lifetime of public service. Among them, in a framed glass case, is an American flag folded in a triangle above the insignias of the five agencies at five levels of government that he worked for: the Federal Bureau of Investigation in Washington DC; the Criminal Justice Information Services Division of the FBI in Clarksburg, Virginia (1996-2001); the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services in Albany (1985-1988); the City of Ithaca Police Department (1988-1996); and the Village of Cayuga Heights (1964-1985). When he retired, the flag was flown at each to honor him.

Since retiring in 2001, Chief McEwen has carried on from the Winthrop Drive home office. For fifteen years, he was a member of the Global Justice Advisory Committee, a federal advisory body to the U.S. Attorney General, and for more than 37 years, beginning in 1978, he chaired the Communications and Technology Committee of the International Association of Chiefs of Police. Currently he is the Tompkins County Public Safety Interoperability Coordinator, a volunteer and non-paid post he has held for a “long time.”

He built the house in 1967, having bought the land on the advice of his father, a banker in Waverly, New York. Ithaca realtors and developers Fay D. Hewitt (1894-1978) and Lagrand Chase (1926-2010) were the builders. They suggested the design include an apartment, which zoning in the Town of Ithaca allowed. That way he could rent out a portion in the years that followed, pay off the mortgage, and build equity. All of which he proceeded to do.

Early Life and Education

Harlin was born in 1937 in Waverly, New York (a village 45 minutes south of Ithaca by car, halfway between Elmira and Binghamton in Tioga County near the Pennsylvania border). By the time he entered his teens he was already showing an interest in his future career. In 1951 he obtained a radio monitor that allowed him to follow local police and fire radio transmissions. A neighbor two houses away from the McEwens, who was Waverly’s volunteer fire chief, let him ride along on fire calls. In those days, in the event of a fire people called for help from alarm boxes placed on street corners. Then a siren would go off at the village hall, and a bell would be rung with the number of rings matched to a specific location. There were two fire stations in Waverly. Whenever young Harlin heard the siren, he ran up to the neighbor’s house and jumped in the car. He especially loved listening to the two-way radio that was the fire department’s means of communication.

Harlin and a brother went to elementary school in Waverly and graduated from its high school. In addition to the experience he gained shadowing the village fire chief, he spent two summers as a Boy Scout camp counsellor and worked at the local Tastee Freez soft ice cream stand. Here was someone interested in people and community life at a young age. He went on to Mohawk Valley Community College, in Utica, which at the time was a technical institute, earning an associate’s degree in retail business. Later, while working in Cayuga Heights, he would obtain a second associate’s degree in criminal justice from Cayuga Community College in Auburn.

Launching a Career

Harlin entered police work in the village where he grew up. He became a part-time officer in the Waverly Police Department in 1957 at the age of 20, then full-time in 1958 after graduating from Mohawk Valley Community College. In February 1959, after he passed the civil service exam which was all that was required for police work at the time, he was appointed permanently in Waverly. In 1962 he was named Deputy Sheriff of Tioga County. While holding that position, he completed the basic police training course that became mandatory after 1959 when New York became the first state to adopt one.

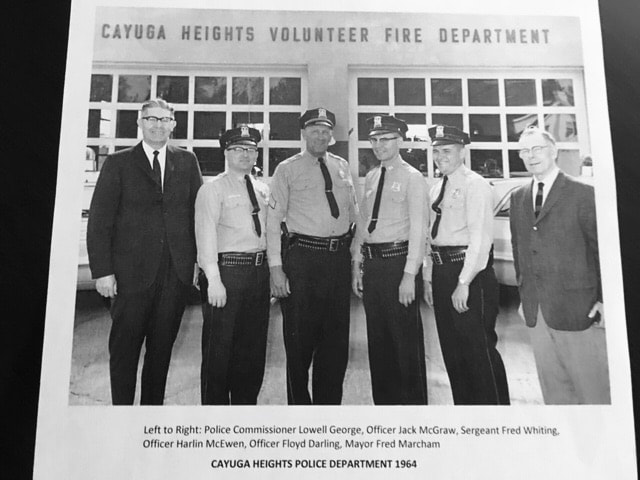

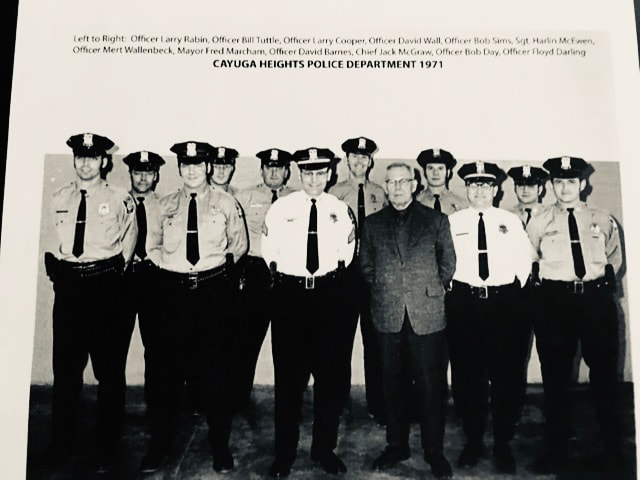

By the early 1960s, he was interested in making a move, and James Herson (1930-2020), then chief of the Cornell University Safety Division, told him about a possible opening in a new police department of the Village of Cayuga Heights. (Since its incorporation in 1915, the Tompkins County sheriff’s department had been providing police services to Cayuga Heights. That worked initially, but after the village quadrupled in size by the annexation of adjoining neighborhoods in 1953, it needed its own.) Lowell George (1915-1980), who held the position of proctor in charge of administering student disciplinary affairs at Cornell, was appointed as a volunteer police commissioner. Between 1958 and 1964, he hired four men: Fred Whiting, Jack McGraw, Floyd Darling and Harlin McEwen. McGraw was named chief in 1968. McEwen, hired in 1964, was promoted from patrol officer to sergeant in 1967, which put him in line to succeed McGraw as chief in 1972. The four-man staff gave the village (population 2,078 in 1960) a full-time police department, but only part-time policing, meaning there were not yet enough men for 24-hour coverage.

The first year after his arrival, Harlin rented a room from the village clerk, Vera Snyder. Then, for two years before he built his house, he lived in the bunk room of the Cayuga Heights fire station that was built at Community Corners in 1956 (194 Pleasant Grove Road). This arrangement prefigured the “bunker” dormitory of the village fire department today. Harlin recalls two students bunking in the old firehouse when he arrived, perhaps Cornell hockey players. In 1965, an article by the publisher of The Town Crier Shopper’s Guide, Ithaca College professor Howard Cogan (1929-2008), featured 28-year-old “Mac McEwen” who was living in the “fire company bunkhouse at the rear of the fire building,” sharing the premises with volunteer fireman Charlie Moran and his family in a separate apartment. Cogan described Harlin as “a bachelor who likes to bowl, water ski and go boating in his “spare time (whenever THAT is!)” and went on to say, “his assigned hours on police patrol are midnight to 8AM.” Both Harlin and Charlie Moran were monitoring not only Cayuga Heights fire calls but Tompkins County Sheriff’s Department calls as well. They were deputized to provide protection for the Town of Ithaca along with the village, just as the Cayuga Heights Fire Department does today.

Second Interview, March 3, 2020

Facilities of the Cayuga Heights Police Department (CHPD)

The four-man force appointed by Lowell George shared an office downstairs in the firehouse with the village clerk. This was a convenient arrangement for Harlin, while he lived in the bunk room at the back of the building until 1966, but very inconvenient for the police when it came time to conduct private interviews. At some point the village board of trustees realized the police department needed its own space, and rooms were leased in 1965 above the shops in the Corners Community Center building at 903 Hanshaw Road (space occupied by the Hage tailoring business today). Lowell George had connections at Cornell. There was no furniture in the space over the stores at the shopping center; he went to the university’s used furniture warehouse and picked out what was needed for the office—tables, desks and chairs. Court was held (with Cornell law school professor Tucker Dean presiding as the village police justice) in the old firehouse. Harlin can remember some of the old shops at 903 Hanshaw Road, such as Bill’s Dairy Bar, owned by Bill Crance where Talbot’s is now. In 1969, Mayor Frederick G. Marcham and the Cayuga Heights Board of Trustees decided the village should have its own building and bought Marcham Hall (the old stone house at Community Corners, 836 Hanshaw Road.) Chief McEwen was given the assignment to design space for the village court there, as well as the police department. The village borrowed funds for the redesign and refurbishment, which allowed him to buy some new furniture. The offices of the village clerks and engineer had to be on the second floor, which, while never wholly satisfactory, was necessary because the police department couldn’t be. The room with a stone fireplace facing the entrance on the first floor of the old building became the chief’s office, and the former kitchen the police department front office. The attached two car garage was rented by Flavin’s Jewelers until 1981. A short time after that Dr. Henry Sutton (1893-1982), a well-known physician, who lived at 126 Sunset Drive in the village, was a gun collector and a good friend of Harlin, died and left a large sum of money the police department, which he loved. George Pfann Jr. was the attorney for the Sutton estate. With the legacy Harlin was able to have a hole broken in the wall between the house and the garage to create the Sutton Conference Room and a locker room for the police.

Second Interview, March 3, 2020

Facilities of the Cayuga Heights Police Department (CHPD)

The four-man force appointed by Lowell George shared an office downstairs in the firehouse with the village clerk. This was a convenient arrangement for Harlin, while he lived in the bunk room at the back of the building until 1966, but very inconvenient for the police when it came time to conduct private interviews. At some point the village board of trustees realized the police department needed its own space, and rooms were leased in 1965 above the shops in the Corners Community Center building at 903 Hanshaw Road (space occupied by the Hage tailoring business today). Lowell George had connections at Cornell. There was no furniture in the space over the stores at the shopping center; he went to the university’s used furniture warehouse and picked out what was needed for the office—tables, desks and chairs. Court was held (with Cornell law school professor Tucker Dean presiding as the village police justice) in the old firehouse. Harlin can remember some of the old shops at 903 Hanshaw Road, such as Bill’s Dairy Bar, owned by Bill Crance where Talbot’s is now. In 1969, Mayor Frederick G. Marcham and the Cayuga Heights Board of Trustees decided the village should have its own building and bought Marcham Hall (the old stone house at Community Corners, 836 Hanshaw Road.) Chief McEwen was given the assignment to design space for the village court there, as well as the police department. The village borrowed funds for the redesign and refurbishment, which allowed him to buy some new furniture. The offices of the village clerks and engineer had to be on the second floor, which, while never wholly satisfactory, was necessary because the police department couldn’t be. The room with a stone fireplace facing the entrance on the first floor of the old building became the chief’s office, and the former kitchen the police department front office. The attached two car garage was rented by Flavin’s Jewelers until 1981. A short time after that Dr. Henry Sutton (1893-1982), a well-known physician, who lived at 126 Sunset Drive in the village, was a gun collector and a good friend of Harlin, died and left a large sum of money the police department, which he loved. George Pfann Jr. was the attorney for the Sutton estate. With the legacy Harlin was able to have a hole broken in the wall between the house and the garage to create the Sutton Conference Room and a locker room for the police.

“Speed Trap,” 1965

Two fatalities caused by speeding in 1965 led to use of radar for enforcement of traffic laws. The village became known as a “speed trap” because of aggressive efforts on the part of the police officers to enforce speed limits.

The Residence Club Fire in 1967

Lowell George assigned Harlin to work full-time for over a year on investigation of the fire at the Cornell Heights Residential Club on Triphammer Road, which took place on April 5, 1967 and caused the deaths of eight university students and one professor. His promotion, to sergeant in September 1967 was, in part, an outcome of that effort. The case remains “cold,” still an open investigation. In Harlin’s opinion the article by N. R. Kleinfeld that appeared in the New York Times Magazine on April 13, 2018 is accurate.

Student Unrest at Cornell in 1969

During the student unrest at Cornell in the 1968-1969 academic year, Harlin recalls that professors living in the village who were considered perhaps conservative being threatened. On his advice, they temporarily moved out of their homes.

First Impressions of Cayuga Heights

Harlin had never even heard of the village when his friend James Herson, who had been a New York State trooper and was directing the Cornell University Division of Public Safety at the time, told him there might be a job opening in Cayuga Heights. He knew where the towns were in the area but not the villages. He became enamored of it because it is so beautiful, both the homes and the people. Outsiders don’t look favorably upon it; they see it as elitist, snobbish, but he found quite the opposite. “I knew all the people, like family.”

Village of Cayuga Heights Police Chiefs, Listed by Year of Appointment

1968 Jack W. McGraw Jr.

1972 Harlin McEwen

1985 David Wall

1998 Kenneth Lansing

2007 Thomas Boyce

2012 James Steinmetz

2108 Jerry Wright

Third Interview, July 20

On the Philosophy of Policing in the Village

Reflecting back on his career, having worked in two (Waverly and Owego) before coming to Cayuga Heights, Harlin concluded that leadership set the tone for the operation of police agencies.

When he arrived in 1964, the village was growing, “slowly but surely.” The Cayuga Heights Police Department (CHPD) was still part-time. Each officer worked an 8-hour shift: four men, five shifts each per week. With a total of 21 shifts in a full work week, the village force was always eight hours short of full coverage. More if someone was on vacation or ill. In times of significant need, someone would get up and go on duty. Emergency coverage was provided by the county sheriff’s office (which had provided policing in the village prior to the creation of CHPD). Eventually an additional officer was hired to achieve full-time coverage in the village, 24 hours, 7 days a week. Of importance: every resident is only three minutes away from police services.

There was no other round the clock service in the village during Harlin’s tenure. If a public services emergency arose, the police would be called—to direct traffic around a downed tree, for example, or to be on location if an electric wire went down. On one occasion, Harlin recalled, a water pipe broke in the home of an elderly lady living alone; he went to her house, turned off the water and called a plumber. In most police agencies this wouldn’t happen. This level of response soon became an expectation on the part of residents. Police would help if a bat flew into a house. “Friendly 24-hour service” sums it up.

The Scope of Police Services

At a certain time, outside criminals started coming into the village, probably in the 1970s, break-ins began to occur. Sophisticated burglars learned there were valuables in village homes. In the early days of electric alarm systems, having researched the cheapest and best ways to use them, Harlin found that PACS (Protective Assurance Control Systems) owned by Gerald Dawson (located at 140 Danby Road) made good, reasonably priced systems. So he recommended them and accompanied someone from the company to meet with homeowners when sales proposals were made. That led to another police service unique in the county; homeowners would give the CHPD a key to use if the alarm went off. Each key was assigned a number, and a great big key ring was kept locked in a police car. This was unheard of elsewhere and reflected the trust in which villagers held members of the police department. The Knox Box system used today is an update of this initial security provision.

Policing was very sparse in the county when Harlin arrived here. The New York State Police had a barracks in Ithaca and could provide services in the daytime or evenings, but not in the middle of the night. Its regional headquarters was located in Horseheads. One or two troopers covered three counties (Tompkins, Chemung and Schuyler); as a result only rarely was someone available in the Ithaca area at night. This situation led to recognition of the need for full-time policing in Cayuga Heights. When CHPD became a 24-hour force, it began to offer help elsewhere, to Lansing for example. Harlin recalls getting a call on one occasion from the county sheriff’s office asking him to go to the Howard Johnson’s motel that was located where Tops, Applebees and other businesses are today. A young guy had come into the lobby and collapsed on the floor. When Harlin arrived and tried to wake him up, the fellow attacked him. They “rolled around” on the floor for a while. The young man turned out to be a runaway from George Junior Republic. A Cornell security officer arrived on the scene and helped take him into custody. The sheriff deputized village police so they could answer such calls outside Cayuga Heights. Today there are more sheriff’s deputies and troopers to cover the area, but at one time, other than the City of Ithaca Police Department, the CHPD was the only full-time policing agency in Tompkins County. For major crimes, such as homicides, additional help is needed. The village department may be in charge, but more manpower is forthcoming from the county and state. There have been times over the years when, because of the tax rate and increasing costs, the need for a full-time police force has been discussed. But in Harlin’s experience villagers have always spoken up in favor of keeping it. There was no police union when Harlin was the chief; he made budget proposals directly to the Board of Trustees. When he left, the department decided they wanted to unionize like other police agencies in our area.

Memories of Frederick G. Marcham (1898-1992)

Harlin was “very fond” of Fred Marcham, mayor of the village from 1956 to 1988. They had a “wonderful relationship,” from the time Harlin was one of the initial four police officers appointed in Cayuga Heights throughout his tenure as chief from 1972 to 1985. Mayor Marcham had an even handed style of management; he was a “calm, reasoned thinker about every issue confronting the village.”

The decision taken by the village to build its own sewer plant (in 1956), which was a “major undertaking,” serves as an example. Former village engineer Jack Rogers (John B. Rogers III, 1923-2018) was central to discussions about it. The plant when built was smaller than it is today, intended to serve only the village, but that soon changed. A contract for waste treatment service was negotiated with the Town of Lansing around the time a sewer line was installed under Route 13 near Howard Johnson’s. The mayor presided over lengthy discussions in the Board of Trustees, and there was tension with the City of Ithaca over the village decision to go it alone and not avail itself of the city sewer treatment facility.

Fred Marcham was a well-regarded professor at Cornell, who “vigorously protected” the village’s interests against encroachments by the university. Cornell University owned land at the south end of Cayuga Heights where there were roughly 13 fraternities and sororities, Harlin recalls. Today fewer are located in the village, the other Greek houses being in the city. There was a difficulty with parties serving alcohol; there were arguments, noise complaints—“a lot of tension.”

There were “many, many difficult conflicts” with the university during the Marcham years. The 1967 residence club fire (see above) took place in a building that was previously an apartment building built by a private developer. The university bought it and converted it into a dormitory for which it wasn’t zoned. There was “a lot of tension” prior to the reaching of an agreement. The university owned the building at the time of the fire under terms of an agreement that Mayor Marcham negotiated.

Regarding the university playing fields at Jessup and Triphammer Roads, the village didn’t want the land used that way. Rezoning was necessary with legal arguments back and forth. Cornell University resented complying with Village of Cayuga Heights zoning. Eventually the village agreed to the playing fields but without lights. After a few years the university wanted them. Parts of Cornell dormitories are located on land where the boundary lines of Cayuga Heights, the Town of Ithaca and the City of Ithaca converge; there are some in each municipality. The university-owned Hasbrouck apartments for graduate students in the Town of Ithaca are served by the Cayuga Heights Fire Department.

Marcham was elected over and over again (biennially for thirty-two years) because he negotiated with Cornell on behalf of village voters with strong leadership. His goal was to keep Cayuga Heights low key and residential. Like them, he wanted to keep the commercial development of Community Corners limited to small mom and pop businesses open in daytime only.

Harlin kept the mayor fully informed about what was going on in the police department. The two of them met regularly in the living room of the Marcham home (112 Oak Hill Road). Fred Marcham was “almost like a father” to him. In 1983 when Harlin was elected president of the New York State Association of Chiefs of Police, the mayor drove to Rochester in order to swear him into office at the organization’s annual conference.

Whenever you are a strong leader, however, someone will oppose you who doesn’t like your judgment and thinking. There were a few such people, who came to complain at monthly Board of Trustees meetings. Such behavior, in Harlin’s opinion, is “to be expected in any government situation. You try to please the most that you can and do the right thing.

Acquiring Marcham Hall

Harlin remembers (in 1969) when because of the “expanding nature of our business” the village bought the building that became the municipal offices (836 Hanshaw Road), later named Marcham Hall. Buying it was “one of the best investments” they could have made. The CHPD needed to be on the ground floor in order to bring in anyone who might be arrested.

Jack Rogers and the Department of Public Works

Jack Rogers (see above) was “a good guardian of the public works of the village,” keeping them in good shape, selecting those in need of attention, and making proposals to the Board of Trustees for repairs. There was never enough money, but he prioritized and took care of roads needing the most attention. The same goes for the replacement of water mains and sewer pipes. I knew Carl Crandall, Jack’s predecessor; he set in place a foundation. Harlin watched the Rogers family grow up.

The Village Clerks

Regarding the village clerks; Harlin remembers working with Vera Snyder from whom he rented a room when he arrived in the village. She was “a nice lady.” Rose Tierney was Vera’s deputy, working in the village offices that existed in the first firehouse. Vera built a home in the village (790 Hanshaw Road) with an apartment in the basement. The clerks were very important figures who needed to know a great deal about laws relating to the village. Other than the police, they were the only full-time employees. Jack Rogers was part-time as the superintendent of public works; working out of his home, he did supervise a full-time work crew. (Snyder was the clerk from 1962 to 1969, succeeded by Rose Tierney until 1978.)

The Fire Chief

The fire chief was a volunteer position, elected by members of the fire company. The fire department was funded by the Village of Cayuga Heights budget. Under contract, the fire department provided service to certain parts of the Town of Ithaca. That, plus village taxes, paid for equipment and protective gear. Bud Quinlan was chief when Harlin arrived. He worked at Cornell and lived in an apartment over the firehouse. Ned Boyce, who ran the gas station at the Corners on the east side of Hanshaw Road, succeeded Bud Quinlan as chief. Ned Boyce was the father-in-law of Skip Morgan, who later took over management of the gas station. Roger Morse (1927-2000), a professor at Cornell who specialized in beekeeping, succeeded Boyce as fire chief; then Dick Vorhis (1913-1989), who worked at Williams Shoe Store on the Commons, succeeded him. Vorhis lived over the firehouse too. At some point it was decided that the position of fire chief was more than volunteer. State requirements became more and more demanding, so a part-time position held by the chief was created to do the bookkeeping. Harlin installed radios in Department of Public Works vehicles and village firetrucks so they could communicate with the police.

Two fatalities caused by speeding in 1965 led to use of radar for enforcement of traffic laws. The village became known as a “speed trap” because of aggressive efforts on the part of the police officers to enforce speed limits.

The Residence Club Fire in 1967

Lowell George assigned Harlin to work full-time for over a year on investigation of the fire at the Cornell Heights Residential Club on Triphammer Road, which took place on April 5, 1967 and caused the deaths of eight university students and one professor. His promotion, to sergeant in September 1967 was, in part, an outcome of that effort. The case remains “cold,” still an open investigation. In Harlin’s opinion the article by N. R. Kleinfeld that appeared in the New York Times Magazine on April 13, 2018 is accurate.

Student Unrest at Cornell in 1969

During the student unrest at Cornell in the 1968-1969 academic year, Harlin recalls that professors living in the village who were considered perhaps conservative being threatened. On his advice, they temporarily moved out of their homes.

First Impressions of Cayuga Heights

Harlin had never even heard of the village when his friend James Herson, who had been a New York State trooper and was directing the Cornell University Division of Public Safety at the time, told him there might be a job opening in Cayuga Heights. He knew where the towns were in the area but not the villages. He became enamored of it because it is so beautiful, both the homes and the people. Outsiders don’t look favorably upon it; they see it as elitist, snobbish, but he found quite the opposite. “I knew all the people, like family.”

Village of Cayuga Heights Police Chiefs, Listed by Year of Appointment

1968 Jack W. McGraw Jr.

1972 Harlin McEwen

1985 David Wall

1998 Kenneth Lansing

2007 Thomas Boyce

2012 James Steinmetz

2108 Jerry Wright

Third Interview, July 20

On the Philosophy of Policing in the Village

Reflecting back on his career, having worked in two (Waverly and Owego) before coming to Cayuga Heights, Harlin concluded that leadership set the tone for the operation of police agencies.

When he arrived in 1964, the village was growing, “slowly but surely.” The Cayuga Heights Police Department (CHPD) was still part-time. Each officer worked an 8-hour shift: four men, five shifts each per week. With a total of 21 shifts in a full work week, the village force was always eight hours short of full coverage. More if someone was on vacation or ill. In times of significant need, someone would get up and go on duty. Emergency coverage was provided by the county sheriff’s office (which had provided policing in the village prior to the creation of CHPD). Eventually an additional officer was hired to achieve full-time coverage in the village, 24 hours, 7 days a week. Of importance: every resident is only three minutes away from police services.

There was no other round the clock service in the village during Harlin’s tenure. If a public services emergency arose, the police would be called—to direct traffic around a downed tree, for example, or to be on location if an electric wire went down. On one occasion, Harlin recalled, a water pipe broke in the home of an elderly lady living alone; he went to her house, turned off the water and called a plumber. In most police agencies this wouldn’t happen. This level of response soon became an expectation on the part of residents. Police would help if a bat flew into a house. “Friendly 24-hour service” sums it up.

The Scope of Police Services

At a certain time, outside criminals started coming into the village, probably in the 1970s, break-ins began to occur. Sophisticated burglars learned there were valuables in village homes. In the early days of electric alarm systems, having researched the cheapest and best ways to use them, Harlin found that PACS (Protective Assurance Control Systems) owned by Gerald Dawson (located at 140 Danby Road) made good, reasonably priced systems. So he recommended them and accompanied someone from the company to meet with homeowners when sales proposals were made. That led to another police service unique in the county; homeowners would give the CHPD a key to use if the alarm went off. Each key was assigned a number, and a great big key ring was kept locked in a police car. This was unheard of elsewhere and reflected the trust in which villagers held members of the police department. The Knox Box system used today is an update of this initial security provision.

Policing was very sparse in the county when Harlin arrived here. The New York State Police had a barracks in Ithaca and could provide services in the daytime or evenings, but not in the middle of the night. Its regional headquarters was located in Horseheads. One or two troopers covered three counties (Tompkins, Chemung and Schuyler); as a result only rarely was someone available in the Ithaca area at night. This situation led to recognition of the need for full-time policing in Cayuga Heights. When CHPD became a 24-hour force, it began to offer help elsewhere, to Lansing for example. Harlin recalls getting a call on one occasion from the county sheriff’s office asking him to go to the Howard Johnson’s motel that was located where Tops, Applebees and other businesses are today. A young guy had come into the lobby and collapsed on the floor. When Harlin arrived and tried to wake him up, the fellow attacked him. They “rolled around” on the floor for a while. The young man turned out to be a runaway from George Junior Republic. A Cornell security officer arrived on the scene and helped take him into custody. The sheriff deputized village police so they could answer such calls outside Cayuga Heights. Today there are more sheriff’s deputies and troopers to cover the area, but at one time, other than the City of Ithaca Police Department, the CHPD was the only full-time policing agency in Tompkins County. For major crimes, such as homicides, additional help is needed. The village department may be in charge, but more manpower is forthcoming from the county and state. There have been times over the years when, because of the tax rate and increasing costs, the need for a full-time police force has been discussed. But in Harlin’s experience villagers have always spoken up in favor of keeping it. There was no police union when Harlin was the chief; he made budget proposals directly to the Board of Trustees. When he left, the department decided they wanted to unionize like other police agencies in our area.

Memories of Frederick G. Marcham (1898-1992)

Harlin was “very fond” of Fred Marcham, mayor of the village from 1956 to 1988. They had a “wonderful relationship,” from the time Harlin was one of the initial four police officers appointed in Cayuga Heights throughout his tenure as chief from 1972 to 1985. Mayor Marcham had an even handed style of management; he was a “calm, reasoned thinker about every issue confronting the village.”

The decision taken by the village to build its own sewer plant (in 1956), which was a “major undertaking,” serves as an example. Former village engineer Jack Rogers (John B. Rogers III, 1923-2018) was central to discussions about it. The plant when built was smaller than it is today, intended to serve only the village, but that soon changed. A contract for waste treatment service was negotiated with the Town of Lansing around the time a sewer line was installed under Route 13 near Howard Johnson’s. The mayor presided over lengthy discussions in the Board of Trustees, and there was tension with the City of Ithaca over the village decision to go it alone and not avail itself of the city sewer treatment facility.

Fred Marcham was a well-regarded professor at Cornell, who “vigorously protected” the village’s interests against encroachments by the university. Cornell University owned land at the south end of Cayuga Heights where there were roughly 13 fraternities and sororities, Harlin recalls. Today fewer are located in the village, the other Greek houses being in the city. There was a difficulty with parties serving alcohol; there were arguments, noise complaints—“a lot of tension.”

There were “many, many difficult conflicts” with the university during the Marcham years. The 1967 residence club fire (see above) took place in a building that was previously an apartment building built by a private developer. The university bought it and converted it into a dormitory for which it wasn’t zoned. There was “a lot of tension” prior to the reaching of an agreement. The university owned the building at the time of the fire under terms of an agreement that Mayor Marcham negotiated.

Regarding the university playing fields at Jessup and Triphammer Roads, the village didn’t want the land used that way. Rezoning was necessary with legal arguments back and forth. Cornell University resented complying with Village of Cayuga Heights zoning. Eventually the village agreed to the playing fields but without lights. After a few years the university wanted them. Parts of Cornell dormitories are located on land where the boundary lines of Cayuga Heights, the Town of Ithaca and the City of Ithaca converge; there are some in each municipality. The university-owned Hasbrouck apartments for graduate students in the Town of Ithaca are served by the Cayuga Heights Fire Department.

Marcham was elected over and over again (biennially for thirty-two years) because he negotiated with Cornell on behalf of village voters with strong leadership. His goal was to keep Cayuga Heights low key and residential. Like them, he wanted to keep the commercial development of Community Corners limited to small mom and pop businesses open in daytime only.

Harlin kept the mayor fully informed about what was going on in the police department. The two of them met regularly in the living room of the Marcham home (112 Oak Hill Road). Fred Marcham was “almost like a father” to him. In 1983 when Harlin was elected president of the New York State Association of Chiefs of Police, the mayor drove to Rochester in order to swear him into office at the organization’s annual conference.

Whenever you are a strong leader, however, someone will oppose you who doesn’t like your judgment and thinking. There were a few such people, who came to complain at monthly Board of Trustees meetings. Such behavior, in Harlin’s opinion, is “to be expected in any government situation. You try to please the most that you can and do the right thing.

Acquiring Marcham Hall

Harlin remembers (in 1969) when because of the “expanding nature of our business” the village bought the building that became the municipal offices (836 Hanshaw Road), later named Marcham Hall. Buying it was “one of the best investments” they could have made. The CHPD needed to be on the ground floor in order to bring in anyone who might be arrested.

Jack Rogers and the Department of Public Works

Jack Rogers (see above) was “a good guardian of the public works of the village,” keeping them in good shape, selecting those in need of attention, and making proposals to the Board of Trustees for repairs. There was never enough money, but he prioritized and took care of roads needing the most attention. The same goes for the replacement of water mains and sewer pipes. I knew Carl Crandall, Jack’s predecessor; he set in place a foundation. Harlin watched the Rogers family grow up.

The Village Clerks

Regarding the village clerks; Harlin remembers working with Vera Snyder from whom he rented a room when he arrived in the village. She was “a nice lady.” Rose Tierney was Vera’s deputy, working in the village offices that existed in the first firehouse. Vera built a home in the village (790 Hanshaw Road) with an apartment in the basement. The clerks were very important figures who needed to know a great deal about laws relating to the village. Other than the police, they were the only full-time employees. Jack Rogers was part-time as the superintendent of public works; working out of his home, he did supervise a full-time work crew. (Snyder was the clerk from 1962 to 1969, succeeded by Rose Tierney until 1978.)

The Fire Chief

The fire chief was a volunteer position, elected by members of the fire company. The fire department was funded by the Village of Cayuga Heights budget. Under contract, the fire department provided service to certain parts of the Town of Ithaca. That, plus village taxes, paid for equipment and protective gear. Bud Quinlan was chief when Harlin arrived. He worked at Cornell and lived in an apartment over the firehouse. Ned Boyce, who ran the gas station at the Corners on the east side of Hanshaw Road, succeeded Bud Quinlan as chief. Ned Boyce was the father-in-law of Skip Morgan, who later took over management of the gas station. Roger Morse (1927-2000), a professor at Cornell who specialized in beekeeping, succeeded Boyce as fire chief; then Dick Vorhis (1913-1989), who worked at Williams Shoe Store on the Commons, succeeded him. Vorhis lived over the firehouse too. At some point it was decided that the position of fire chief was more than volunteer. State requirements became more and more demanding, so a part-time position held by the chief was created to do the bookkeeping. Harlin installed radios in Department of Public Works vehicles and village firetrucks so they could communicate with the police.