205 Oak Hill Road

Year Built: 1929

Architect: J. Lakin Baldridge

Style: Tudor

Full House History: Mark Eisner, "A History of 205 Oak Hill Road, Cayuga Heights, Ithaca, New York"

The early history of student activism at Cornell, in the late 1950s, is associated with the history of this handsome 1929 brick, stone, and stucco house. In 1958, Cornell President Deane Malott and his wife were living in the home. (Cornell University first rented and then purchased the home from Leverett Saltonstall Jr., son of the Massachusetts senator, as temporary housing for the incoming Cornell president.)

Kirkpatrick Sale, who grew up nearby at 309 The Parkway and went on to become a prolific author on environmentalism, politics, and other subjects, was a leader of a Cornell student protest outside the Malott's home. At issue was a university policy forbidding unchaperoned parties in off-campus housing, which the protestors thought was the "last straw" in attempted control over student life. Sale and his Cornell roommate, Richard Fariña, who fictionalized the era in his 1966 novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, were part of the protest. Fariña's friend, Thomas Pynchon, described the scene at the house in the introduction to Fariña's book:

Year Built: 1929

Architect: J. Lakin Baldridge

Style: Tudor

Full House History: Mark Eisner, "A History of 205 Oak Hill Road, Cayuga Heights, Ithaca, New York"

The early history of student activism at Cornell, in the late 1950s, is associated with the history of this handsome 1929 brick, stone, and stucco house. In 1958, Cornell President Deane Malott and his wife were living in the home. (Cornell University first rented and then purchased the home from Leverett Saltonstall Jr., son of the Massachusetts senator, as temporary housing for the incoming Cornell president.)

Kirkpatrick Sale, who grew up nearby at 309 The Parkway and went on to become a prolific author on environmentalism, politics, and other subjects, was a leader of a Cornell student protest outside the Malott's home. At issue was a university policy forbidding unchaperoned parties in off-campus housing, which the protestors thought was the "last straw" in attempted control over student life. Sale and his Cornell roommate, Richard Fariña, who fictionalized the era in his 1966 novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, were part of the protest. Fariña's friend, Thomas Pynchon, described the scene at the house in the introduction to Fariña's book:

"This extraordinary meddling [by the university in student private life] was not seriously protested until the spring of 1958, when, like a preview of the '60s, students got together on the issue, wrote letters, rallied, demonstrated, and finally, a couple of thousand strong, by torchlight in the curfew hours between May 23rd and 24th, marched to and stormed the home of the University president. Rocks, eggs, and a smoke bomb were deployed. Standing on his front porch, the egg-spattered president vowed that Cornell would never be run by mob rule. He then went inside and called the proctor, or chief campus cop, screaming, "I want heads! . . . I don't care whose! Just get me some heads, and be quick about it!" So at least ran the rumor next day, when four upperclassmen, Farina among them, were suspended. Students, however, were having none of this--they were angry. New demonstrations were suggested. After some dickering, the four were reinstated. This was the political and emotional background of that long-ago spring term at Cornell." Thomas Pynchon, introduction to Richard Farina, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, Random House, 1966.

The student protest was likely an impetus to move the next Cornell president farther north in the Village and away from the campus boundary, to Robin Hill.

Protests such as these set the stage for the much more serious student radicalism to come, including the controversial Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Kirkpatrick Sale went on to write the most comprehensive book about the history of SDS.

Another Cayuga Heights resident was an active member of the radical SDS Weathermen. Robin Palmer, who lived at 206 Oak Hill Road, facing the President's house, was later imprisoned for his role in plotting the bombing of a New York City bank.

Another Cayuga Heights resident was an active member of the radical SDS Weathermen. Robin Palmer, who lived at 206 Oak Hill Road, facing the President's house, was later imprisoned for his role in plotting the bombing of a New York City bank.

The Sale and Palmer families were both vital members of the Cayuga Heights' community.

Palmer's parents--paleontologist Katherine V. W. Palmer and Cornell rural education professor E. Laurence Palmer--are remembered for transferring to Cornell University what is now known as Palmer Woods, the beautiful natural preserve across the street from the Palmers' house, along Triphammer Road. John Marcham (112 Oak Hill Road) remembers playing "Capture the Flag" in what was then called "Punky's Woods" when he was a young boy.

Palmer's parents--paleontologist Katherine V. W. Palmer and Cornell rural education professor E. Laurence Palmer--are remembered for transferring to Cornell University what is now known as Palmer Woods, the beautiful natural preserve across the street from the Palmers' house, along Triphammer Road. John Marcham (112 Oak Hill Road) remembers playing "Capture the Flag" in what was then called "Punky's Woods" when he was a young boy.

|

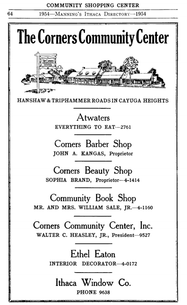

Kirkpatrick Sale's parents--Cornell English professor William M. Sale Jr. and Helen Sale--owned the Community Book Shop at Community Corners.

Looking back fondly on his youth spent in the Village, Sale published an article in 2009 in the Front Porch Republic called Growing Up Village in which he describes how the Village influenced his views on the subject of "human scale." |

"The fact that my end of Cayuga Heights blended in with some farms as it went northward, not all of them working but still with open fields where birds sang and fireflies danced in droves, also had some effect on me growing up. I used to skate and play hockey on the pond at one place where the old farmer never even seemed to venture outside in the winter, and I would ride my bike down dirt roads that seemed to lead nowhere past farmhouses and barns that varied from spanking neat to decrepit. Somehow I had the sense that I was connected to people who knew the land, knew how to grow things (besides a Victory Garden like my father had), had some solidity and longevity in place (unlike my family, new to the village)." Kirkpatrick Sale, "The Importance of Growing Up Village," Front Porch Republic, May 29, 2009.